Porous Pavement in Parking Lot Helps Township Meet MS4 Requirements

It’s National Water Quality Month, and we’re sharing projects we’ve designed that help improve water quality in the communities we serve. Today, we’re profiling the West Caracas Avenue parking lot in Derry Township.

This 40,000 square foot parking lot includes 11,500 square feet of porous asphalt, which reduces the volume of stormwater runoff, prevents pollutants from entering the watershed, and promotes groundwater recharge.

What is porous pavement?

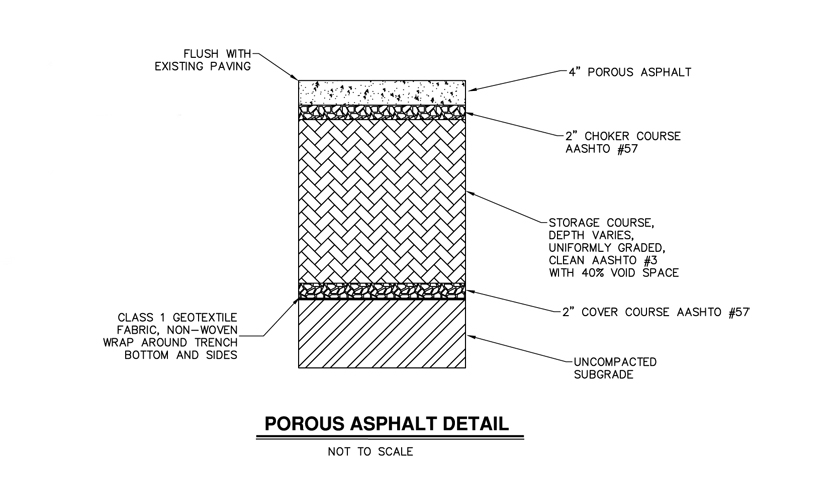

Porous pavement (a.k.a. pervious pavement) comes in many forms: concrete, asphalt, paver blocks, reinforced turf, recycled glass, and more. Traditional asphalt and concrete is densely packed with fine materials, but porous pavement uses coarser materials and a higher percentage of air voids in between these materials. A clean stone bed consisting of 1 inch to 3 inch stone with a high void ratio is installed below the porous surface to provide temporary runoff storage and allow for infiltration.

The space in between the coarser material provides a place for water to seep through to the soil underneath.

What are the advantages of porous pavement?

It can trap solids and pollutants that otherwise would’ve been carried to lakes and streams by stormwater collected in inlets. These pollutants seep through the pavement into a bed of rocks below, where they undergo the natural cleansing process that has purified our stormwater for hundreds of years before asphalt and concrete were invented.

It reduces stormwater runoff, thereby reducing the need for stormwater detention basins and stormwater infrastructure. Porous pavement allows the rain water to infiltrate the ground; therefore, it reduces the volume of stormwater runoff. This can reduce the number of inlets and storm pipes a client needs to be build (and reduce construction cost associated with that infrastructure).

See water infiltrate the porous pavement parking stalls almost immediately, while water collects on the conventional pavement outside the stall.

It can reduce flooding risks. Heavy rains can be absorbed into the ground instead of overloading inlets and detention basins.

It recharges the groundwater. Rain is absorbed back into the water supply, rather than being collected, stored and released from a detention basin.

It reduces the heat island effect of paved surfaces because air can circulate better through this material.

It reduces winter maintenance since the stone bed below the porous pavement tends to absorb and retain heat allowing snow to melt faster. So typically light snow and ice accumulation are handled with little to no maintenance.

What should you consider before investing in porous pavement?

It is coarser than traditional paving materials, but it is still fine enough to meet ADA standards and most people cannot tell the difference in appearance.

It must be carefully designed by engineers to work properly. The designer needs to know how quickly the soil beneath the pavement can absorb water (some soils absorb more quickly than others) and design the paving surface and stone bed accordingly. Otherwise, water can build up underneath the surface and can cause damage or surface flooding. Also, porous pavement is ideally suited for flatter surfaces to promote stormwater absorption and minimize the stone bed depth. On steeper surfaces benching or terracing of the stone bed is needed to maintain a reasonable stone bed depth and minimize excavation.

Maintenance requirements are different than they are for traditional pavement, depending on the material chosen. Certain materials require frequent vacuuming to prevent the voids or “pores” from being clogged. Sand or cinders should not be applied on or adjacent to porous pavement. More advanced materials – like elastomerically bound glass – have reduced maintenance needs.

Its strength rating is lower than traditional paving materials due to the increased air content. Therefore, it is not recommended for surfaces that will see heavy volumes of traffic or loading areas that will be frequented by large trucks. However, as the popularity of porous pavement continues to grow, many paving companies are developing higher strength materials.

What are the best uses for porous pavement?

Due to the lower strength of porous paving materials, it is best used for low-volume applications like:

- Parking spaces

- Residential alleys/roads

- Residential driveways

- Sidewalks and Walking paths

- Tennis Courts

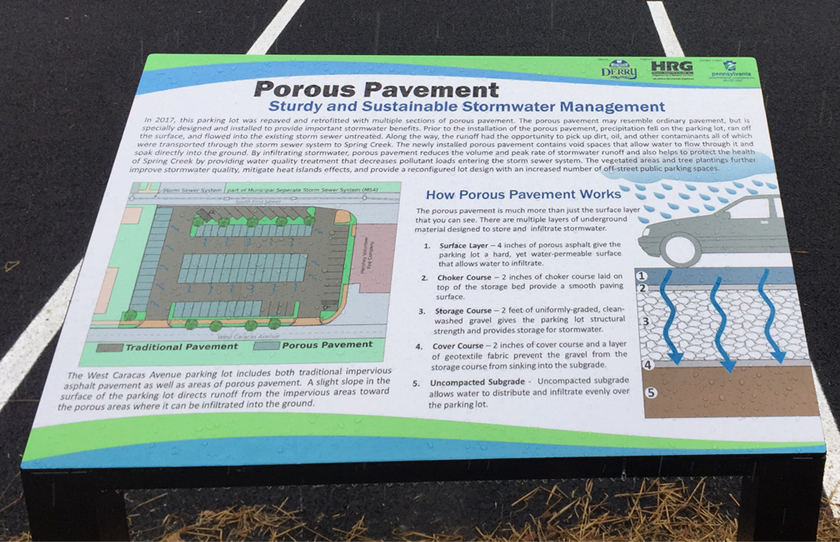

Derry Township chose to pursue porous pavement in the West Caracas Avenue parking lot to meet the requirements of its MS4 stormwater management program and reduce the possibility of flooding. The porous pavement and vegetative islands in the lot are designed to completely infiltrate the runoff from a 100-year storm event and reduce the amount of sediment, nitrogen and phosphorous entering the watershed. This helps the township meet its Chesapeake Bay pollutant reduction plan goals.

Informational signage educates the public about the various Best Management Practices (BMPs) used in the lot and the benefits of infiltration to water quality. This helps the township meets the MCM #1 (public education) goal of its MS4 permit.

DEP awarded the township a $200,000 Local Stormwater BMP Implementation Grant, which covered almost half of the project cost.

But the new parking lot provides other benefits to the community besides improved water quality. It also accommodates more cars and has better access from local streets, too. This is important because it’s located in a busy section of downtown Hershey, where it serves visitors to the local restaurants, the Hershey Story museum, the Hershey Theater, and many local shops. It also accommodates Life on Chocolate events in ChocolateTown Square.

The West Caracas Avenue parking lot project shows that development and environmental benefits can peacefully coexist and be affordable for communities at the same time. Municipalities don’t have to choose between protecting water quality and promoting economic development; they just have to invest wisely.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities. James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.