WEBINAR: How to Cut Stormwater Costs with Partnerships & Collaboration

/in Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Water Resources, Uncategorized /by Judy LincolnCommunities report increased flooding in recent years – even outside the flood zone.

Aging infrastructure is at or near the end of its useful life, and signs of failure are appearing.

Regulatory agencies are requiring communities to do more to manage stormwater, but additional funding is not being provided.

These are big problems, and most communities can’t solve them alone. Collaboration is the key to keeping the cost of stormwater improvements manageable, and this webinar will show you how to make collaboration work for your community.

Our financial services practice area leader Adrienne Vicari joined Jim Cosgrove of Kleinfelder, Inc. and the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters to discuss the benefits of collaboration and offer tips communities can use to form effective partnerships. She identifies specific entities for partnership (including other municipalities, state and federal agencies, property owners, and a variety of non-profit organizations) and shows real world examples of how partnerships are saving municipalities millions of dollars on stormwater management and MS4 compliance.

Watch this free webinar below and contact Adrienne Vicari to discuss partnership opportunities for your community.

How Recreational Partnerships Deliver More Value for Local Communities

/in Insights-Landscape Architecture, Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Recreation /by Judy LincolnBridge Management Systems: Safer Bridges with a Longer Lifespan at a Reduced Cost

/in Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Transportation /by Judy Lincoln5 Economic Benefits of Parks and Recreational Facilities

/in Insights-Landscape Architecture, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Planning, Insights-Recreation, Uncategorized /by Judy Lincoln5 Reasons You Should Consider a Roadway Pavement Management Program

/in Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Transportation, Uncategorized /by Judy LincolnPorous Pavement in Parking Lot Helps Township Meet MS4 Requirements

/in Insights-Municipal, Insights-Water Resources /by Judy LincolnIt’s National Water Quality Month, and we’re sharing projects we’ve designed that help improve water quality in the communities we serve. Today, we’re profiling the West Caracas Avenue parking lot in Derry Township.

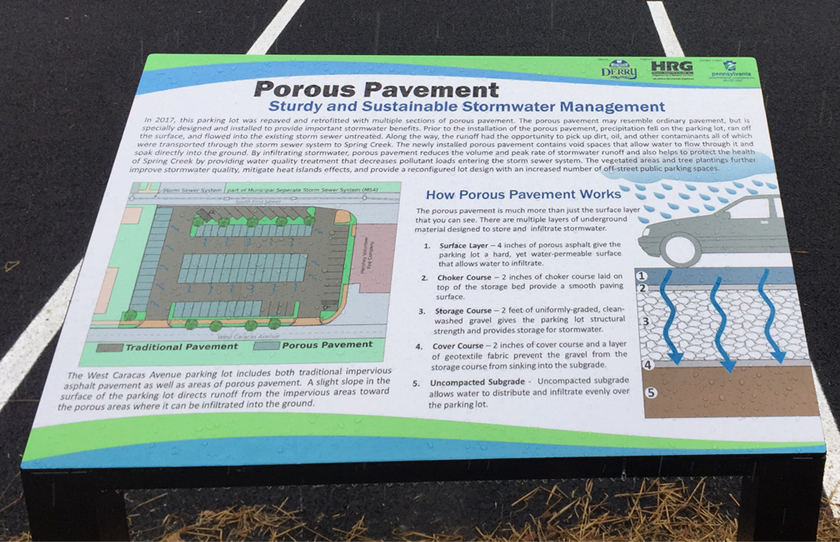

This 40,000 square foot parking lot includes 11,500 square feet of porous asphalt, which reduces the volume of stormwater runoff, prevents pollutants from entering the watershed, and promotes groundwater recharge.

What is porous pavement?

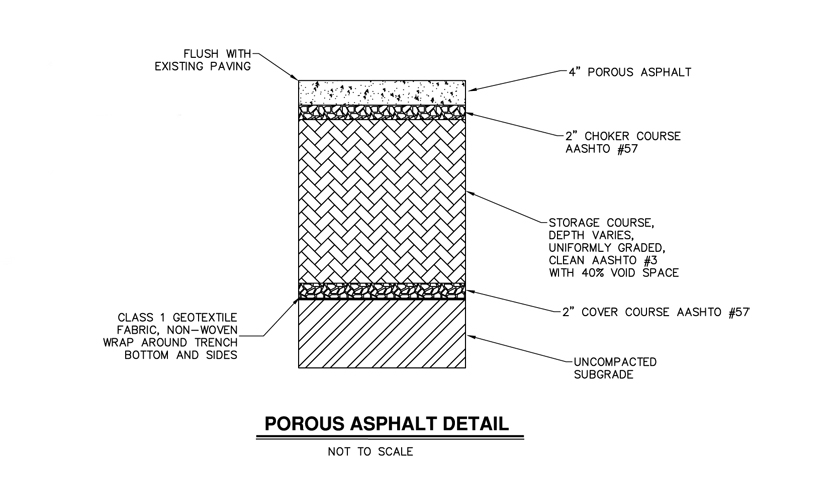

Porous pavement (a.k.a. pervious pavement) comes in many forms: concrete, asphalt, paver blocks, reinforced turf, recycled glass, and more. Traditional asphalt and concrete is densely packed with fine materials, but porous pavement uses coarser materials and a higher percentage of air voids in between these materials. A clean stone bed consisting of 1 inch to 3 inch stone with a high void ratio is installed below the porous surface to provide temporary runoff storage and allow for infiltration.

The space in between the coarser material provides a place for water to seep through to the soil underneath.

What are the advantages of porous pavement?

It can trap solids and pollutants that otherwise would’ve been carried to lakes and streams by stormwater collected in inlets. These pollutants seep through the pavement into a bed of rocks below, where they undergo the natural cleansing process that has purified our stormwater for hundreds of years before asphalt and concrete were invented.

It reduces stormwater runoff, thereby reducing the need for stormwater detention basins and stormwater infrastructure. Porous pavement allows the rain water to infiltrate the ground; therefore, it reduces the volume of stormwater runoff. This can reduce the number of inlets and storm pipes a client needs to be build (and reduce construction cost associated with that infrastructure).

See water infiltrate the porous pavement parking stalls almost immediately, while water collects on the conventional pavement outside the stall.

It can reduce flooding risks. Heavy rains can be absorbed into the ground instead of overloading inlets and detention basins.

It recharges the groundwater. Rain is absorbed back into the water supply, rather than being collected, stored and released from a detention basin.

It reduces the heat island effect of paved surfaces because air can circulate better through this material.

It reduces winter maintenance since the stone bed below the porous pavement tends to absorb and retain heat allowing snow to melt faster. So typically light snow and ice accumulation are handled with little to no maintenance.

What should you consider before investing in porous pavement?

It is coarser than traditional paving materials, but it is still fine enough to meet ADA standards and most people cannot tell the difference in appearance.

It must be carefully designed by engineers to work properly. The designer needs to know how quickly the soil beneath the pavement can absorb water (some soils absorb more quickly than others) and design the paving surface and stone bed accordingly. Otherwise, water can build up underneath the surface and can cause damage or surface flooding. Also, porous pavement is ideally suited for flatter surfaces to promote stormwater absorption and minimize the stone bed depth. On steeper surfaces benching or terracing of the stone bed is needed to maintain a reasonable stone bed depth and minimize excavation.

Maintenance requirements are different than they are for traditional pavement, depending on the material chosen. Certain materials require frequent vacuuming to prevent the voids or “pores” from being clogged. Sand or cinders should not be applied on or adjacent to porous pavement. More advanced materials – like elastomerically bound glass – have reduced maintenance needs.

Its strength rating is lower than traditional paving materials due to the increased air content. Therefore, it is not recommended for surfaces that will see heavy volumes of traffic or loading areas that will be frequented by large trucks. However, as the popularity of porous pavement continues to grow, many paving companies are developing higher strength materials.

What are the best uses for porous pavement?

Due to the lower strength of porous paving materials, it is best used for low-volume applications like:

- Parking spaces

- Residential alleys/roads

- Residential driveways

- Sidewalks and Walking paths

- Tennis Courts

Derry Township chose to pursue porous pavement in the West Caracas Avenue parking lot to meet the requirements of its MS4 stormwater management program and reduce the possibility of flooding. The porous pavement and vegetative islands in the lot are designed to completely infiltrate the runoff from a 100-year storm event and reduce the amount of sediment, nitrogen and phosphorous entering the watershed. This helps the township meet its Chesapeake Bay pollutant reduction plan goals.

Informational signage educates the public about the various Best Management Practices (BMPs) used in the lot and the benefits of infiltration to water quality. This helps the township meets the MCM #1 (public education) goal of its MS4 permit.

DEP awarded the township a $200,000 Local Stormwater BMP Implementation Grant, which covered almost half of the project cost.

But the new parking lot provides other benefits to the community besides improved water quality. It also accommodates more cars and has better access from local streets, too. This is important because it’s located in a busy section of downtown Hershey, where it serves visitors to the local restaurants, the Hershey Story museum, the Hershey Theater, and many local shops. It also accommodates Life on Chocolate events in ChocolateTown Square.

The West Caracas Avenue parking lot project shows that development and environmental benefits can peacefully coexist and be affordable for communities at the same time. Municipalities don’t have to choose between protecting water quality and promoting economic development; they just have to invest wisely.

Reduce the Cost of MS4 Compliance and Pollutant Reduction Plans Through Cooperation

/in Insights-Local Government, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Water Resources, Uncategorized /by Judy Lincoln

Stormwater management has become a major priority for environmental agencies over the past decade, and communities are struggling to meet the increasing requirements to reduce stormwater pollutants and runoff volume. The cost is simply too high for many municipalities to bear alone, but it becomes much more manageable if municipalities can share the burden with their neighbors.

Take the Pollutant Reduction Plan requirement of the MS4 application as an example. If a municipality submits a Pollutant Reduction Plan on its own, it is limited to constructing BMPs within its own borders or the drainage way of its impaired streams, but DEP will generally accept the construction of BMPs anywhere within the watershed for an MS4 permit that is submitted by a regional cooperative. This means cooperating municipalities can install BMPs that yield the greatest pollutant load reduction for the lowest cost.

Usually the largest expense associated with BMP construction is the cost of acquiring land on which to build the BMP. An individual municipality may not have much land on which to build, particularly if it is an urban municipality in which most of the available land has already been developed. As a result, the municipality may be forced to implement a large number of BMPs that each provide only marginal individual benefit in order to meet the pollutant reduction goal. If a municipality submits a regional plan with other communities in the same watershed, it will have access to a much greater land area on which to build BMPs and a reduced need for right-of-way acquisition and easements. This allows the participating municipalities to build the most effective water quality measures in the places with the greatest need.

Any improvements in upstream water quality will lead to improvements in downstream water quality, so a municipality can still see improvements in its water quality using a watershed-based approach even if a particular BMP is not located within that municipality’s borders.

When BMPs are constructed on a watershed-wide basis, the construction cost is typically lower due to economies of scale, and the water quality results are better.

Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) is working with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority on a regional stormwater collaboration that includes 32 municipalities in Luzerne County. These municipalities intend to meet 70% of their sediment reduction goal with a single BMP: conversion of existing flood control levees into a constructed wetland with a sediment forebay and a meandering stream channel.

Regional cooperation can save municipalities money in other ways besides BMP construction. For example, the cost of preparing the Pollutant Reduction Plan itself will be much lower as a result of cooperation due to economies of scale.

Hiring a consultant to assist with pollutant reduction planning can cost thousands of dollars. If that cost is shared with 10 other municipalities, each individual municipality only has to pay a small portion.

It’s like sharing your first apartment with two roommates when you were in your 20s. The fixed cost of rent and utilities is the same whether one person lives there or three, but each person pays less if they can split that cost three ways (instead of renting their own individual apartments).

Stormwater management involves many fixed costs like the cost of owning equipment to clean out inlets or conduct outfall inspections.

Spreading those costs across a greater number of users means each user pays a smaller price for service.

Another way cooperation can reduce the cost of stormwater management is by giving municipalities increased purchasing power. Generally, you can negotiate lower unit costs for items when you buy them in larger quantities. For example, cooperating municipalities could replace or slip line several miles of pipe for a lower cost if the work was completed as part of a larger, regional project. These savings apply to the bidding of services, too. The municipalities working with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority saved hundreds of thousands of dollars on base mapping (i.e. orthophotography, impervious area, etc.) by participating with WVSA under a single project (rather than having each municipality bid its own contract).

Municipalities have greater purchasing power when they cooperate on stormwater management solutions. For example, cooperating municipalities could slip line several miles of pipe for a lower cost if the work was completed as part of a larger, regional project.

A regional cooperative also has more borrowing power than a single municipality, and funding agencies are more likely to award a grant or loan to a regional project than one submitted by a single municipality. Funding agencies prefer regional projects because they believe regional cooperation streamlines costs, and politicians tend to support projects that benefit as large a constituent base as possible. A regional initiative should be tied together by legal agreements that assure the funding agency all funding will be properly administered. (These legal agreements are also required to meet DEP requirements for submission of a regional pollution reduction plan.)

This post is an excerpt from a longer article in the July-August-September issue of Keystone Water Quality Manager magazine. The article is focused on the cost savings communities enjoy by cooperating with regional partners on their stormwater management programs. Read the magazine for advice on finding partners for your stormwater management program or contact us to request a copy.

Erin G. Letavic, P.E., is the regional manager of civil engineering services in HRG’s Harrisburg office. She guides municipalities and cooperative groups throughout Pennsylvania through the management of their MS4 permits, provides grant application development and administration services, and provides retained engineering services to local government.

Adrienne Vicari, P.E. is the financial services practice area leader at Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG). She provides strategic financial planning and grant administration services to numerous municipal and municipal authority clients. She also serves as project manager for several projects involving the creation of stormwater authorities or the addition of stormwater to the charter of existing authorities throughout Pennsylvania.

Capital Improvement Planning Helps Londonderry Township Improve Bridge Conditions At Lower Cost

/in Insights-Municipal, Insights-Planning, Insights-Transportation /by Judy Lincoln

We regularly hear about the condition of infrastructure in the United States, and many times the news is bad. Too often we hear about underground pipes breaking, roads crumbling, and bridges that need to be closed. Fortunately, in Londonderry Township, bridge conditions are actually pretty good.

Londonderry Township is specifically responsible for 13 bridges, all of which cross waterways and are less than 20’ in length. Closing any one of these bridges for safety concerns could cause a significant disruption to emergency access and general traffic flow. To avoid this, Londonderry Township asked HRG to assess all 13 structures and prioritize their maintenance and replacement needs. Our evaluation indicated that all 13 bridges were likely more than 50 years old, and six of them should be replaced within the next 3 – 10 years.

HRG worked with the township to create an approach to address this pressing infrastructure need without overburdening the township’s annual budget. The initial concept was to replace one bridge every other year for the six most critical structures. This would allow us to address the township’s most urgent needs without being forced into an emergency situation. It would also allow us to identify alternative funding for each bridge replacement and carefully plan any necessary road closures to minimize traffic interruption.

Londonderry’s program is a perfect example of infrastructure asset management and capital improvement planning. HRG has written extensively about the benefits of asset management and capital improvement planning. Essentially, a proactive approach to identifying infrastructure needs, prioritizing those needs, and planning for the necessary funding produces better infrastructure at a lower lifetime cost.

Thanks to this forward-looking approach, Londonderry Township is about to replace the last of the original six critical structures: a bridge on Swatara Creek Road. This project is funded through the partial use of a Dauphin County Local Share Gaming Grant.

Three bridges were replaced in 2016: one each on Beagle, Braeburn, and Hollendale Roads. The township bundled these bridges into one project and used extremely favorable funding from the Dauphin County Infrastructure Bank. The first two bridges were replaced in 2012. Only one – on Round Top Road, was planned, but a second bridge on Foxianna Road required replacement after flooding from Tropical Storm Lee undermined the bridge. Fortunately, because of the emergency nature of the bridge replacement, the township was able to use federal disaster relief funding.

With the replacement of the six most critical bridge structures complete, the township will be able to focus on regular maintenance of the remaining seven structures to extend their useful life as long as possible. A proactive approach to maintenance like this means better driving conditions for township drivers over a longer period of time. The bridges will last longer, and the need for replacement will be delayed. This will save the township hundreds of thousands of dollars over time. (See an illustration of how this works with actual budget dollars in our article Better Roads for Less Money with Asset Management.)

The upkeep of bridges can seem like a daunting and expensive task, but it’s actually fairly simple if communities take a proactive approach. Consistent inspections to identify deterioration, regular maintenance to avoid worsening problems, and advanced planning for eventual replacement all combine to simplify bridge upkeep and ensure it remains affordable.

When it does come time for Londonderry Township to replace one of its structures, they will use the same judicial approach to ensure the infrastructure needs of the township are met in an economical manner.

(A version of this article originally appeared in the Londonderry Township newsletter.)

Andrew Kenworthy, P.E., is the eastern region vice president of HRG. He has more than 25 years of experience in municipal engineering and land development/site design.

Andrew Kenworthy, P.E., is the eastern region vice president of HRG. He has more than 25 years of experience in municipal engineering and land development/site design.

How to Incorporate Green Infrastructure into Parks in order to Save Money Meeting Regulatory Requirements

/in Insights-Environmental, Insights-Landscape Architecture, Insights-Municipal, Insights-Recreation, Insights-Water Resources /by Judy LincolnThis article is the third in a series on incorporating green infrastructure into parks and recreational space in order to more cost-effectively meet environmental regulatory requirements. (Part 1 explained why parks are an ideal location for green infrastructure projects to meet regulatory requirements, and Part 2 explained the benefits of incorporating green infrastructure into parks.)

In this article, we provide advice on how communities can identify areas in their park and recreational spaces that are good candidates for green infrastructure and how to work with other groups to get these projects implemented. This article is an excerpt from an article we published in the April 2018 issue of Borough News magazine entitled “Parks Provide the Ideal Location for Meeting Environmental Regulatory Requirements.”

How can municipalities incorporate green infrastructure into their park facilities?

Start by taking an inventory of your facilities and look for places where green infrastructure could be used.

Pay close attention to your hard surface areas. These are the areas that generate the most runoff, so look for ways to reduce the amount of hard surface area or lessen its impact by directing runoff to pervious areas.

Look at your parking lots: How does stormwater flow across the lot? Are there landscaped areas or medians where you could incorporate bioretention facilities? Are there places where you could plant additional trees? Perhaps you could use permeable pavement in the parking stalls.

Watch this video to see a demonstration of how quickly permeable pavement in these municipal parking stalls absorbs a few buckets of water compared to the non-permeable pavement outside the parking stalls.

Do you have paved trails and walkways in your park system? Consider permeable pavement or a tree canopy that runs alongside the path. Because of their linear nature, bioswales can be planted alongside trails or paved paths, too. The following video shows how a system of bioswales along the bike trail in Indianapolis absorbs water during a rain event.

The Magnificent Bioswales & Stormwater Treatment Along the Indy Cultural Trail from STREETFILMS on Vimeo.

Could your athletic fields be used for a dry extended detention basin?

Do you have open space within existing drainage areas that could be used for constructed wetlands?

Do you have a community center? This would be a great location for a demonstration rain garden, rainwater harvesting system, or planter boxes. It could even be a candidate for a green roof.

Middletown Borough reduced the volume of stormwater entering their stormwater system by converting the traditional garden located between their municipal building and parking lot to a rain garden. By redirecting the building downspout to the rain garden, the stormwater that previously flowed across the parking lot is now infiltrated on site.

Check out this article in the Middletown Press and Journal about Middletown’s rain garden.

Successfully integrating green infrastructure into your park facilities is a team effort. Municipal administration, public works staff, planners, and the parks and recreation department should all work together to find cost-effective solutions that maximize benefits for the community.

But the teamwork shouldn’t end inside the government offices. Schools, conservation groups, gardening clubs, and other community groups may also want to lend a hand. Bringing them on board marshals additional resources for the cause and helps to build public support for the efforts.

Your municipal engineer can provide valuable guidance on design, regulatory requirements and even potential funding sources.

Municipal staff must be creative stewards of both the environment and the taxpayers’ money. Incorporating green infrastructure and streambank restoration projects into park and recreational facilities helps them do both. By using land the municipality already owns, communities can greatly reduce the cost of construction projects needed to comply with environmental regulation like the MS4 program. The native plantings used in rain gardens and bioswales typically need less maintenance and chemicals than turf grass, and rainwater collected in barrels can be used for irrigation or toilet flushing in order to lower water consumption costs.

At the same time, these projects prevent pollutants in stormwater runoff from reaching our lakes and streams, preserving them for recreational uses like fishing and swimming. They also help to prevent flooding, which ensures the parks department will be able to keep athletic fields and parks open for scheduled activities after a storm.

In these ways, green infrastructure can enhance the recreational experience for the user. It can also enhance the aesthetic appeal: Rain gardens and native vegetation can provide a habitat for wildlife and butterflies for safe public viewing and can serve as a quiet retreat for reflection.

Signage turns these features into an educational experience and helps to meet the educational outreach requirements of a community’s MS4 permit.

Working together as a team, municipal officials, planners, park professionals, and local community groups can protect our resources while providing exceptional recreational experiences for all.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

Learn more about our work with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority in this 3-part series published in The Authority, a magazine published by the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association.

Learn more about our work with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority in this 3-part series published in The Authority, a magazine published by the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association.