This post is an excerpt from an article we published in the April 2018 issue of Borough News magazine entitled “Parks Provide the Ideal Location for Meeting Environmental Regulatory Requirements.”

Parks aren’t just for fun and relaxation. They deliver significant value to the community, increasing property values, promoting health and wellness, and providing a gathering spot for people to socialize and get to know their neighbors. Did you know they can also help your municipality address environmental concerns like flooding, water pollution, and streambank erosion? This makes them an ideal location for meeting the regulatory requirements contained in the MS4 program.

The latest round of permitting added a new requirement for many municipalities to quantify the level of pollutants they are contributing to the watershed and execute a plan to reduce that level by as much as 10%. Municipalities can meet these requirements by implementing Best Management Practices (BMPs) like green infrastructure and streambank stabilization projects.

The most expensive part of these projects is often buying the land on which to build, so why not use land the municipality already owns in its parks and recreational facilities?

Green Infrastructure

The wide expanses of open space that parks contain are a natural fit for BMPs like green infrastructure.

Green infrastructure uses plants, soils and engineered materials to mimic the processes that absorb water and filter pollutants in nature.

When rain falls on developed property, it sits on the pavement or is directed into pipes and inlets.

Concentrating the water in this way contributes to erosion, and, when too much rain falls at once, those pipes can be overwhelmed. Then flooding occurs. In urban areas, the rain water often carries trash and other pollutants into the waterways, as well.

This is not the case in nature. Rain water that falls on undeveloped land is absorbed into the ground. Plants and vegetation filter chemicals and other pollutants from the water before it can reach our lakes and streams. Green infrastructure seeks to replicate this process.

Examples of green infrastructure include:

- Rain gardens

- Bioswales

- Permeable Pavement

Rain gardens are shallow basins lined with water-tolerant native plants and amended soil media that collect and absorb stormwater runoff. They are also sometimes called bioretention or bioinfiltration basins.

By BrianAsh at English Wikipedia(Uploads) (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

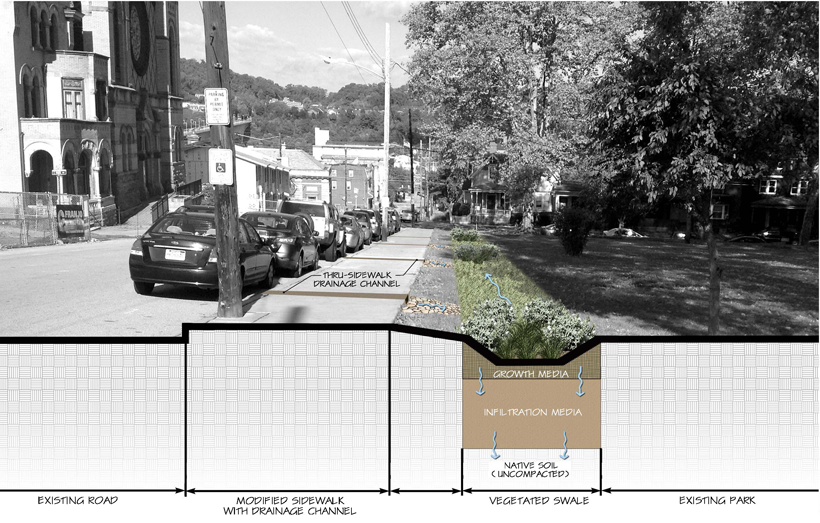

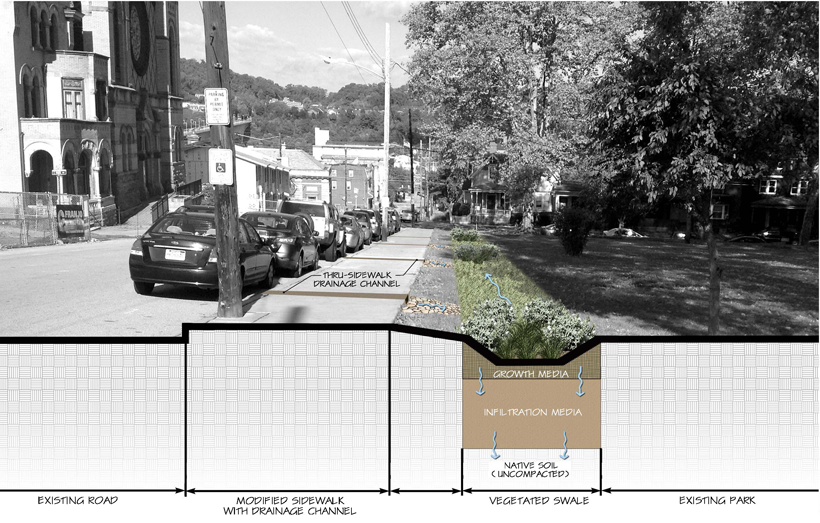

Bioswales are similar to rain gardens, but they are lined with plants that also filter pollutants from the runoff before it is absorbed into the ground. They are typically long and narrow and are thus well-suited for placement along streets and parking lots.

HRG helped identify green infrastructure opportunities for the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority (ALCSOSAN) that would help them address stormwater issues. This is a rendering of a bioswale in Frick Park along Amity Street in Homestead.

Permeable pavement is asphalt or concrete that is made to infiltrate runoff. Unlike conventional asphalt, permeable pavement is porous, and those pores allow water to seep into the ground. Often a layer of aggregate or stones is placed underneath the surface pavement to help filter and store the water before it is absorbed into the soil.

Volunteers demonstrate how permeable pavement in the parking lot of a shopping center absorbs the water.

Other examples of green infrastructure include tree canopies and rainwater harvesting systems.

Streambank Stabilization

Since many parks are already located along streams, they are particularly well-suited for streambank stabilization projects. In a fully developed community that lacks the open space needed for traditional land-based BMPs, a streambank restoration project in a municipal park offers the greatest opportunity for the community to meet its pollutant reduction goals.

This is the case for New Cumberland Borough in Central Pennsylvania. As part of its 2018 permit application, New Cumberland was required to prepare a Chesapeake Bay Pollutant Reduction Plan. In this plan, the borough had to demonstrate how it will reduce its sediment load as part of a multi-state effort to clean up the bay. The borough proposes to meet a significant part of that goal by planting a riparian forest buffer. This buffer will extend the length of the borough park along the Yellow Breeches Creek toward the creek’s confluence with the Susquehanna River. The buffer will slow down stormwater runoff and even absorb some of it in order to reduce further erosion of the streambank.

A streambank restoration project HRG designed in Cranberry Township’s Graham Park

Incorporating green infrastructure and streambank stabilization projects into municipal park and recreational facilities helps to lower the cost of BMP construction for MS4 compliance, but it has many other benefits, too. In our next article, we’ll discuss more of the benefits of incorporating green infrastructure and streambank stabilization into park and recreational facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

Learn more about our work with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority in this 3-part series published in The Authority, a magazine published by the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association.

Learn more about our work with the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority in this 3-part series published in The Authority, a magazine published by the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities.

Ben Gilberti, P.E., manages civil engineering services provided by Herbert, Rowland & Grubic, Inc. (HRG) throughout Western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. He assists with the design of municipal infrastructure like sidewalks, stormwater systems, and sewer facilities. James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.

James Feath, R.L.A., is a senior landscape architect at HRG. He has 20 years of experience in the planning and design of public spaces, including parks, trails, and recreational facilities.